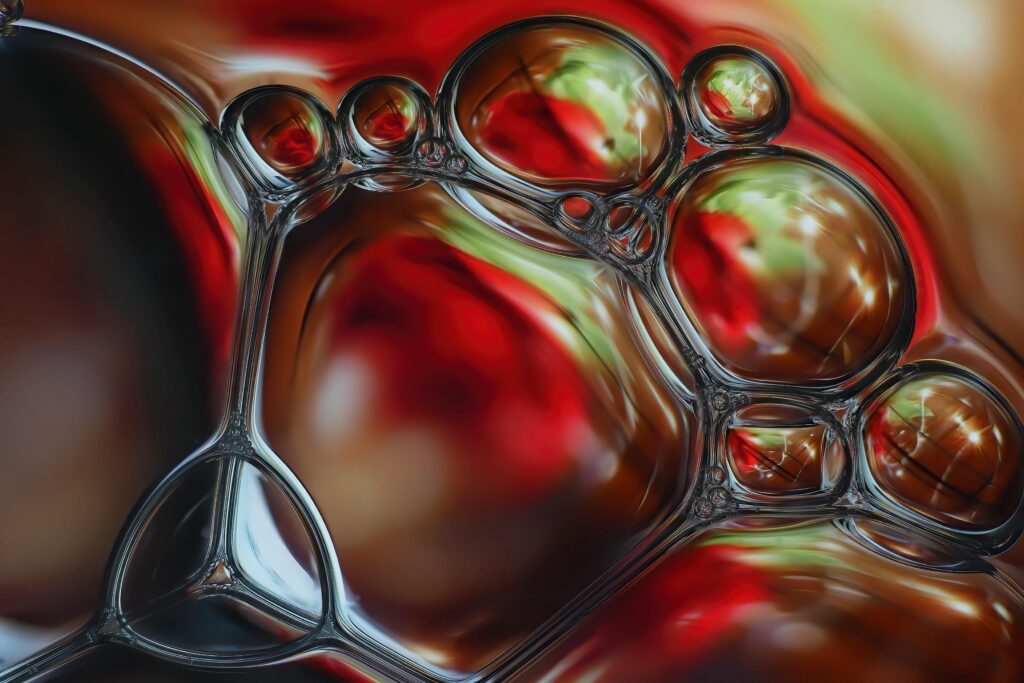

Language is almost immaterial but more than just a sound wave. It exists too as a series of puffs, pockets of air. We use our breath to inflate a balloon, to blow bubbles, to sing an opera. For speaking too, the chit-chat of daily life, we are the choreographers of our own exhalations. We used not to feel those small pockets of air until we began wearing masks. Squeezed, deformed, as personal mist our words clung to our glasses. Exercises made us puff, breathe in repeated short gasps. Language too is made of small pockets of air, barely noticeable, hidden within the sound of speech.

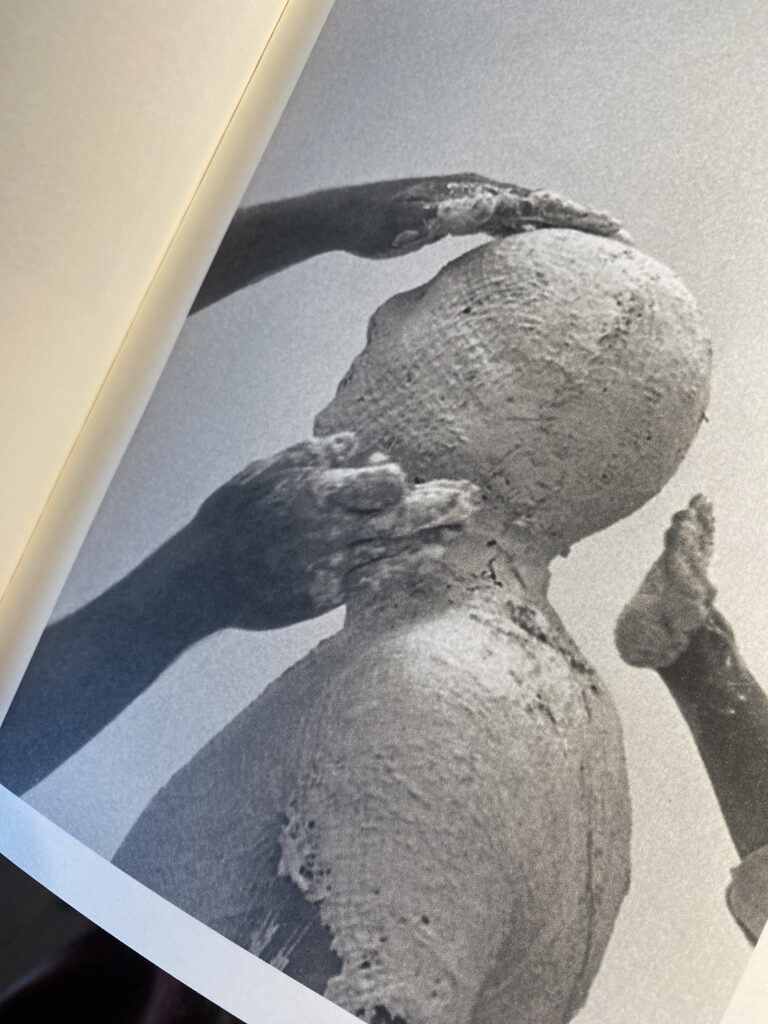

The sculptor Antony Gormley discusses the breath in his writings. He is inspired by Jain, Hindu and Buddhist sculpture from the third century BC up to the 12th century AD. In this tradition life is expressed through breath. Gormley translates this as ‘an implied inner potency expressed in the compound curves of an invented’, abstract body. He tried to use this idea and states ‘in my moulds there is an implied inner pressure’. His is a critique of sculpture as a representation of movement, as action is only ‘a crude expression of life’. This leaves us with an image of breath as a space within us and space for sculpture.

Gormley presents us with the idea that the body is as much about imagination and potential as it is about appearance. Three things he says, intrigue me most – ‘art has been so obsessed by the way light falls on objects’; ‘is there a way that art can go beyond the skin of things?’; ‘I think we limit ourselves by being obsessed by the way things look’. Gormleyan body of imagination and potential is ‘most powerfully expressed by pneuma, the feeling of breath, an internal pressure which links with the tension between immanent and manifest’. Gormley adds that pneuma ‘is not about action but about being’: ‘it is an empty case indicating a human space in space’. Gormley’s pieces are less image than ‘a place in space’ – ‘nothing to do with action, but everything to do with potential’. He pays attention to the air itself, in his words, ‘the atmospheric pressure between the space that is displaced’ (by his sculpture) and ‘the space that surrounds it’. He invites us to identify with that potential. In my words, identify with both an inner potency and those squeezed pockets of air that surround the compound curves of Gormley’s bodies. Identify not with an image, but with inertia, displaced space and pressure.

Before I return to the topic of language as breath, I re-visit aspects of Gormley’s practice. He worked with monks at a monastery in Shaolin, China and mentions Qigong as ‘a concentration on internal balance and breath’. He attempts to bring something from the monks’ practice to his sculptures. For me, Gormley’s breath seems like a quiet felt pressure. I bear in mind the repeated process of casting his own body in plaster in his studio. This means absolute stillness for about an hour and a half, facilitated by his training in Vipassana meditation. He calls it ‘a total concentration on maintaining stillness’. As a child of the 1950’s he recalls the ‘enforced rest’ after lunch, and adds ‘I wasn’t going to move’, I was going to ‘do this thing’. Enforced immobility through rest and later work as a sculptor of his own body evokes that stillness for us.

Gormley’s siesta or meditation during plaster casting brings us into contact with a particular form of stillness. He states his work is not expressionist, it does not come from arbitrary abstraction. Instead it ‘is rooted in a particular example of a human experience of embodiment’. Indeed, it is particular when we think about Gormley’s breath. Here we do not encounter him doing exercises that make him puff, or singing loudly in the shower. No panting Gormley, but composed, Buddha-like, his breath reduced to the minimal. His is a potential of displaced air, minute pressures, compound curvatures. An invitation for us to feel our own lives more intensely. The power of Gormley’s sculpted stillness frees us.

To indicate a ‘human space in space’ through sculpture, brings us back to the human body, that space of pneuma. ‘Pneuma’ can be translated from Greek as both ‘breath’ and ‘air in motion’. ‘Pneuma’ could also be the pockets of air of a speaking subject, almost immaterial, a series of brief atmospheric pressures just outside us. Those may not accentuate a human shape, but bring about associations to another, organic world. Trying to sculpt the pneuma of speech, that quintessentially human potential, leads to questions about the almost immaterial. A mould for thinly woven gauze, bubbles in copper lace, carefully draped knitted material, inflated, clear, flexible silicone? This would be no arbitrary abstraction either. A choice of form rooted in particular, human experiences of embodied speech, of language I would hope. Unencumbered by a mask.

References

Gormley, Anthony (2015). On Sculpture. Edited by Mark Holborn. Thames & Hudson

pp. 78, 166, 16, 48, 190, 168, 32, 49, 79, 168

Gormley, Antony (2012). TED Sculpted space, Within and Without. https://www.ted.com/talks/antony_gormley_sculpted_space_within_and_without?subtitle=en

Sources Images

Image 1: Pixabay

Image 2: Pixabay

Image 3: Photo Alex Pillen Gormley (2015), p. 33

Image 4: Pixabay

Image 5: Crafts Council Handling Collection, 5.9.2024, me holding a piece by Anita Bruce