Sources: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_K-3375, Dostoevsky, F. 1872 The possessed, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_hieroglyphs#/media/File:Minnakht_01.JPG

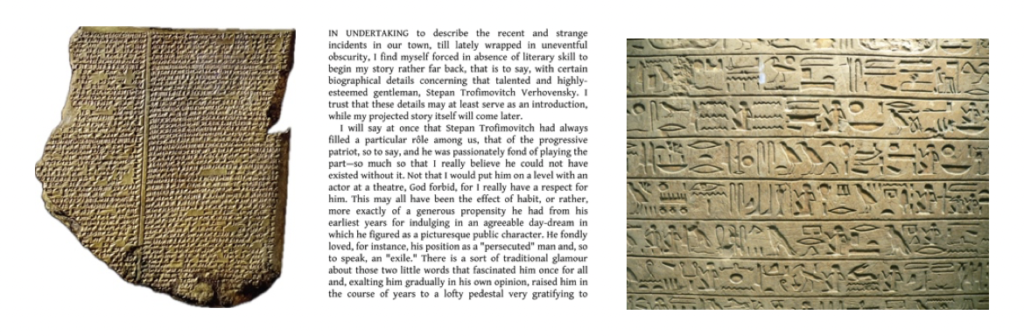

We often imagine language as words on a page, in a shape dictated by our writing system. This could be a square or a rectangle depending on the size of the paper. In ancient times, this would have been the shape of a clay tablet for the Assyrians, or the size of the surfaces of temples or tombs for the Egyptians. Take a page from a novel, its text spread between the four corners of the page, a familiar image, that does not make us think twice.

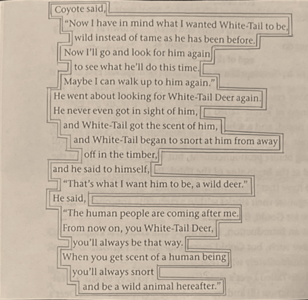

Source: Sketch based on Hymes 2003: p. 239.

People speak in verses not prose though, and this determines the shape of spoken language. There is a brief pause at the end of a phrase, sometimes used to breathe. This punctuates speech. The intonation of speech is another way to mark the boundaries between verses. The voice may rise or fall at the end of each verse, and this creates a pattern, a pattern of verses. Speech can be recorded and then written down to reveal its shape. This can be done for many different genres of speech, such as story telling in everyday life. When written down, speech does not look like prose, its shape on the page resembles poetry. It is important to render this shape accurately.

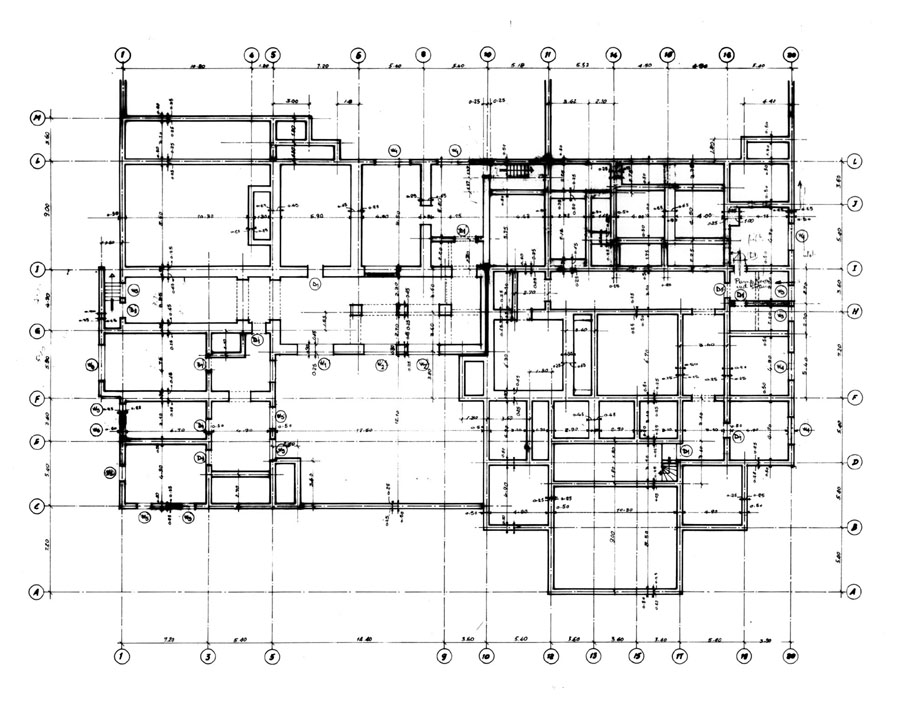

Source: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Floor_plan

We can visualise a way of speaking, its patterns on the page. This requires careful listening, an ear trained for spoken discourse. This can be compared to an architect drawing a floorplan, a projection of complex shapes into a 2-dimensional representation. When producing a written record of spoken language there are conventions that guide this representation of ‘the shape of speech’. Verses are carefully carved out from the flow of speech, laid down on paper, moved to the next line after a pause or small change of intonation. The organisation of verses on the page looks very different from the squares or rectangles of written language in books or on screens. Discovering the verses in spoken language leads to an understanding of the structure of language that is otherwise not possible. This is the groundwork that ought to be done, before we begin to think about pivotal pronouns or monumental grammar in our daily speech habits.

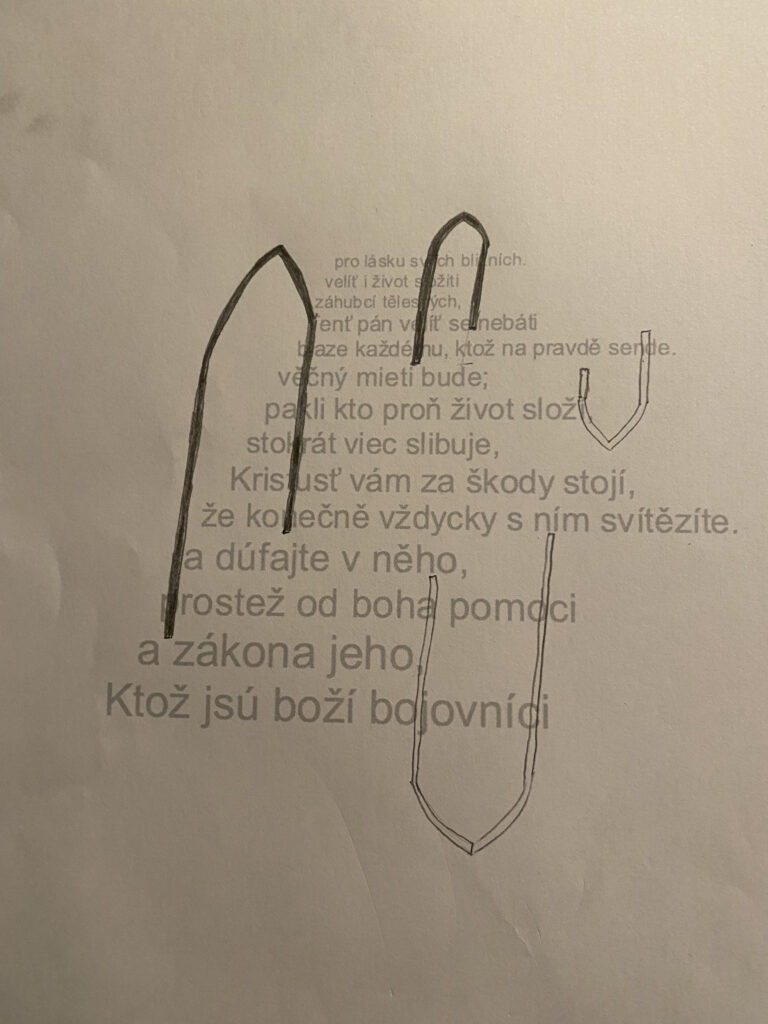

Source: Sketch based on https://www.karaoketexty.cz/texty-pisni/lidove-pisne/ktoz-jsu-bozi-bojovnici-404098

When the linguist Roman Jakobson coined the term monumental grammar he evoked an image in the mind of the reader. The grammatical structure of a poem led him to discern upright arcs as well as inverted arcs within the architecture of its language. There is an almost geometric order to the poem, laid out on the page to be studied by a linguist, almost in 3D. I say ‘almost’ as the poem still features as words on a page, its shape determined by the conventions of writing one line after another, the placement of each verse aligned with the left of the page. In this manner, Jakobson discerns small grammatical units distributed in a pattern across the poem. The connection between these small units is then imagined as arcs across the poem, across the page. There may be another way of representing and thinking about such patterns? Other ways of drawing the verses that emerge along a timeline as we speak? To visualise the ‘slots for reality’ engendered in language centred around the axis of time?

References

Hymes, D. (1994). Ethnopoetics, oral-formulaic theory, and editing texts. Oral Tradition 9: 330–370

Hymes, D. (2003). Now I only know so far: Essays in ethnopoetics. University of Nebraska Press.

Jakobson, R. (1981) Selected writings III Poetry of grammar and grammar of poetry. Edited, with a preface by Stephen Rudy. Mouton Publishers.

(p. 96)