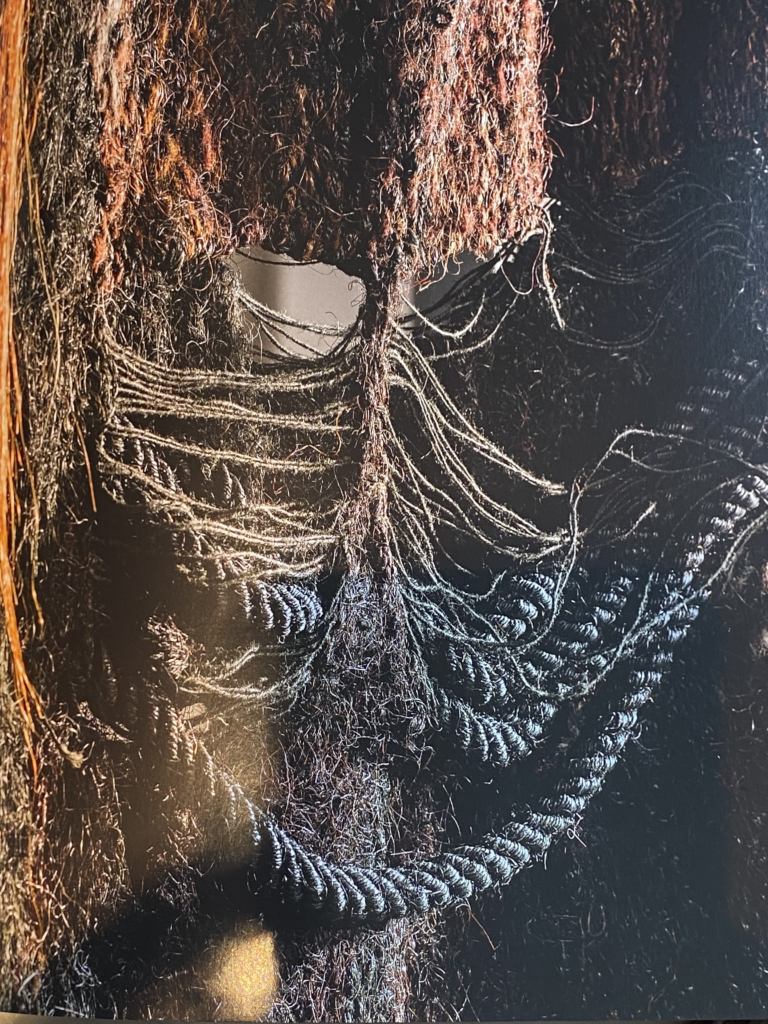

SOURCE: ALEX PILLEN PHOTO – COXON 2022: 63

This is one of my favorite quotes: language is ‘the most massive and inclusive art we know, a mountainous and anonymous work’ of countless generations. It dates back to the 1920s and offers us a rare visual image of the totality of language – all of it taken together as a mountainous work of art. Every new word, every new way of speaking is thereby recognized as the creation of an individual person. Innovative language use is then later picked up by others. What is at stake is everybody’s daily linguistic creativity which is seldom highlighted by scholars. This is what is meant by ‘the most inclusive art we know’. Not only can languages be traced back over millennia, but all of us play a role today in their continuing growth and adaptation. Language is an inclusive art that is massive indeed.

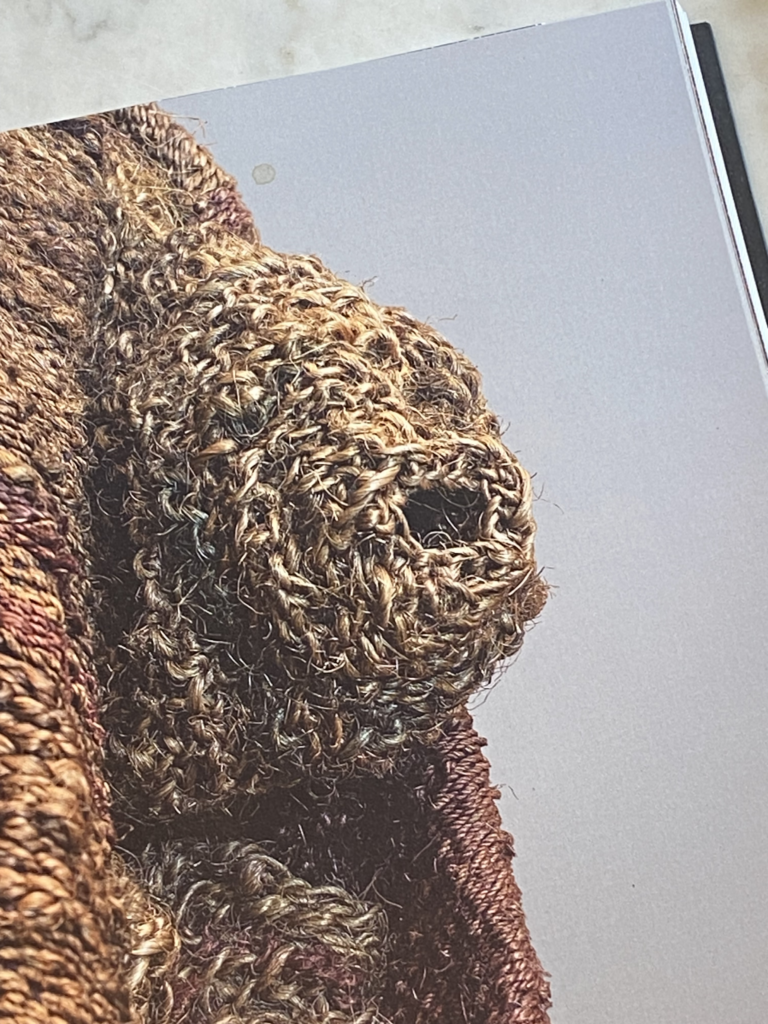

SOURCE: ALEX PILLEN PHOTO – COXON 2022: 105

The multi-dimensionality of language compels me to envisage it as an organic object. An ancient metaphor for language as thread emphasized a linearity, language unfolding along the line of time. Written language is framed by the edges of the page, as text or ‘woven material’ metaphorically encompassed by a loom. I propose to first consider the work of two fibre artists to begin to explore materials and techniques that would enable me to transcend both linearity and frame in order to explore organic shapes in natural language. By choosing fibre I pay tribute to ancient metaphors, not only of language as thread, but also the intertwining of two strands, and images of language as twine, yarn, cord.

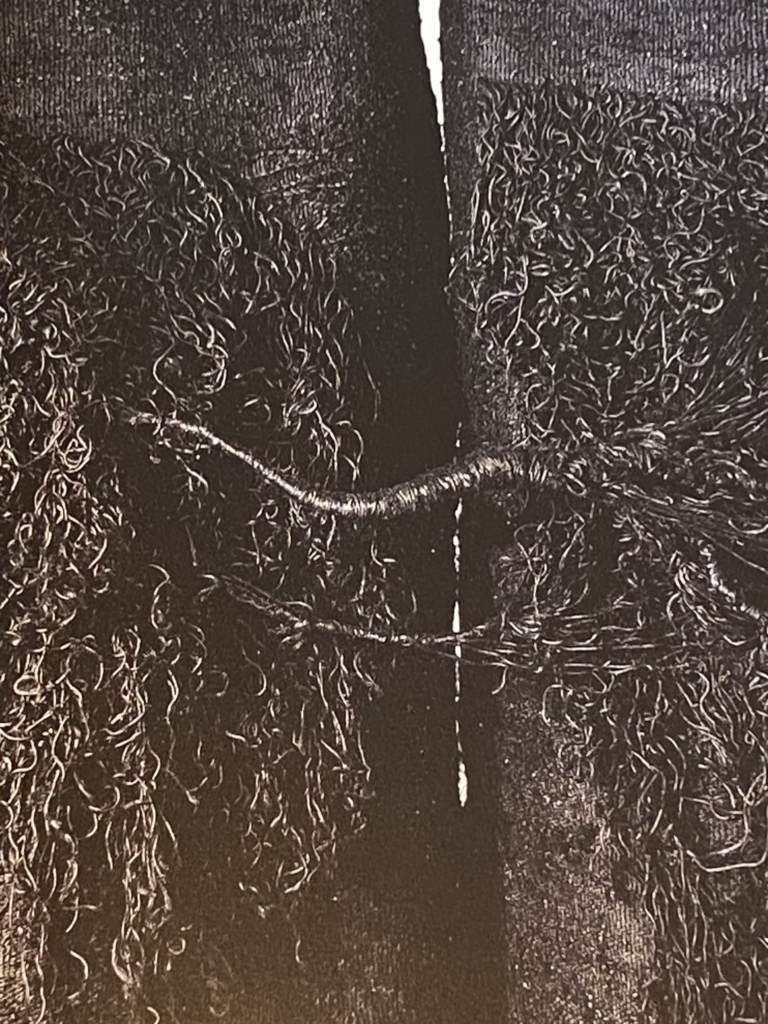

SOURCE: ALEX PILLEN PHOTO ‘RUDRA’ – BARBICAN 2024: 237

‘Rudra’ is a piece that is truly inspiring. Knotted and twisted in dyed hemp in 1982 by Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949-2015) this is an imposing figure. As a fibre sculpture of the Rigvedic god Rudra it evokes his powers which were intended to incite a feeling of respect mixed with fear or wonder. Mukherjee’s giant biomorphic figures made out of natural fibre emerged knot by knot. The variegated tones used to dye the hemp, the fibre’s modulating hues add further definition to these multi-dimensional forms. Monumental creatures feature rippling contours, folds and protrusions. Such fibre sculptures exceed human scale, their presence and epic size invoke a sense of awe and reverence for spectators that could be anywhere in the world. The artist Mukherjee talks about eliciting a ‘sacred feeling’ regardless of people’s religious and cultural background. What I bear in mind when thinking about a mountainous entirety of language visualized as a cloak of fibre, is Mukherjee’s choice of material, and above all the epic size that may be required.

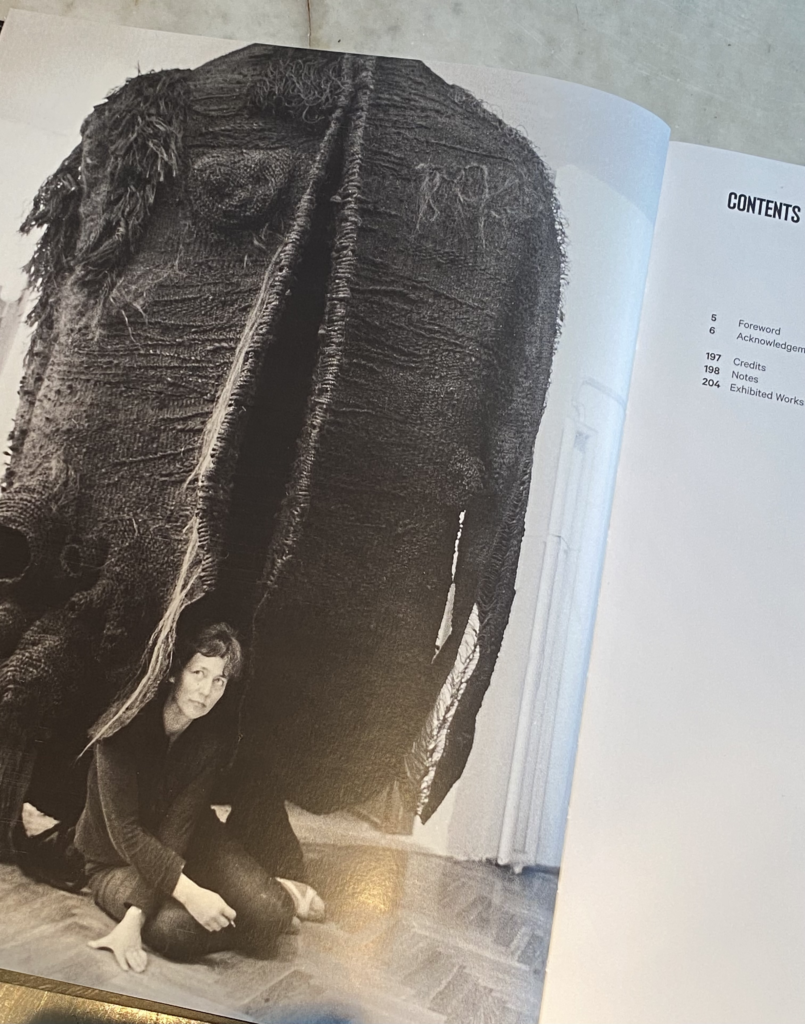

SOURCE: ALEX PILLEN PHOTO – COXON 2022: 98

Another point of reference are the ‘Abakans’ of course. This is a rare instance where a form of contemporary art in all its uniqueness is named after an artist, Magdalena Abakanowics (1930-2017). Abakans are large overpowering structures hung from the ceiling made from woven fibre that are made to look like ancient beings. These organic textile forms seem to roam freely in space. They are free form and ‘off-loom’ weaves. For me this technique appears like an opportunity to release natural language from its frames. The Abakans have a commanding physical presence, and evoke forms and textures from the natural world. Abakanowics used raw natural material; sisal, wool, burlap, horsehair, or rope made from natural fibre. Abakans are made to appear like living and breathing organisms. Apart from the fact that they are fibrous, large sculptures I am intrigued by the fact that viewers are invited to enter the artworks and immerse themselves in their reverberating spaces – almost feel draped into an earthy tactile figure. The artist recognized that only through doing this people could fully understand them.

SOURCE: ALEX PILLEN PHOTO – COXON 2022: 2

As I imagine chunks of language as large fibrous structures and envisage further material metaphors for the architectures of language, I rely on the legacy of the oeuvres of both Mukherjee and Abakanowics. Their multi-dimensional organic objects have a certain weight to them. What I am looking for, by contrast, is light, airy materials and shapes that reflect the ethereal quality of natural language. For now I am experimenting with thin copper wire, to which I can add small amounts of organic fibre as and when needed. I am looking for something that reverberates in the air, almost like sound.

SOURCE: ALEX PILLEN PHOTO – COXON 2022: 137

References

Barbican Exhibition (2024). Unravel. Munich, London, New York: Prestel.

pp. 196-197, 236-239

Coxon, Ann & Mary Jane Jacob (2022). Magdalena Abakanowics. London: Tate Publishing

pp.2, 63, 98, 104, 137

Johnstone, B. (2000). The individual voice in language. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29, 405–424.

p. 409

Jhavery, Shanay (2019). Mrinalini Mukherjee. Mumbai: The Shoestring Publisher.

Sapir, E. (1921). Language. An introduction to the study of speech. Harcourt, Brace.

p. 235